The Importance of Vocabulary for Reading Comprehension

When it comes to reading comprehension, vocabulary knowledge is essential. Without a strong vocabulary, readers may struggle to make sense of the texts they encounter. But why is vocabulary so important, and how can parents and educators help build it effectively?

Vocabulary: The Key to Unlocking Meaning

Research shows that a rich vocabulary enhances both basic understanding and deeper comprehension. Readers use vocabulary to grasp the literal meaning of a text and to infer hidden messages. Both types of understanding depend on a reader’s knowledge of words.

Vocabulary, Mental Imagery, and Cognitive Development

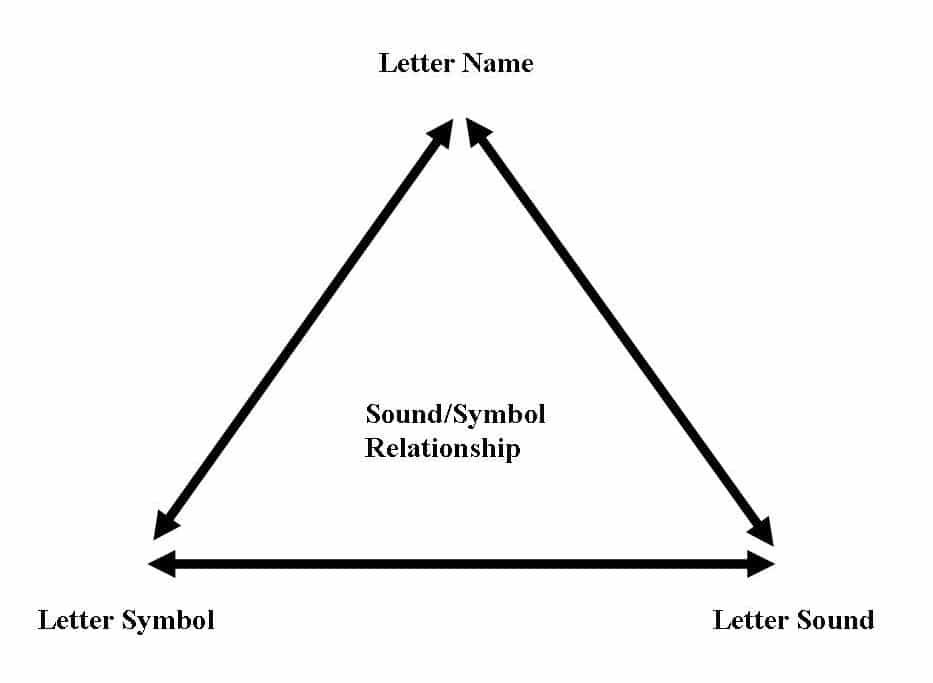

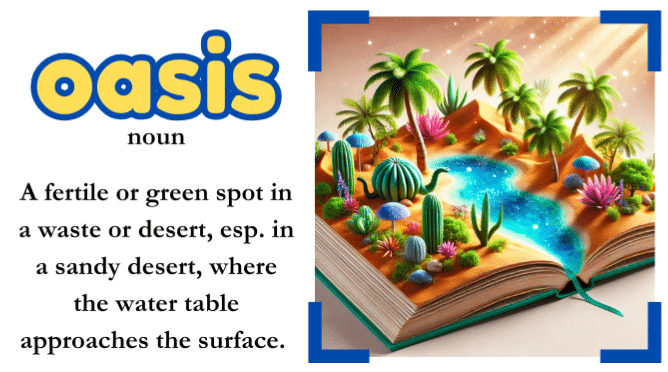

Mental imagery strengthens the connection between vocabulary and comprehension. Descriptive words help readers create pictures in their minds, making the text more engaging and easier to remember. For instance, phrases like “lush forest” or “towering skyscraper” trigger vivid mental images, enhancing understanding and creating a richer reading experience.

Building Vocabulary: Strategies for Success

Here are some practical strategies to support vocabulary development:

- Read Aloud Together: Reading aloud introduces children to new words in context. Choose books slightly above their independent reading level to help expand their vocabulary.

- Encourage Wide Reading: Provide access to a variety of materials, including fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and informational texts. Different genres introduce unique words and ideas.

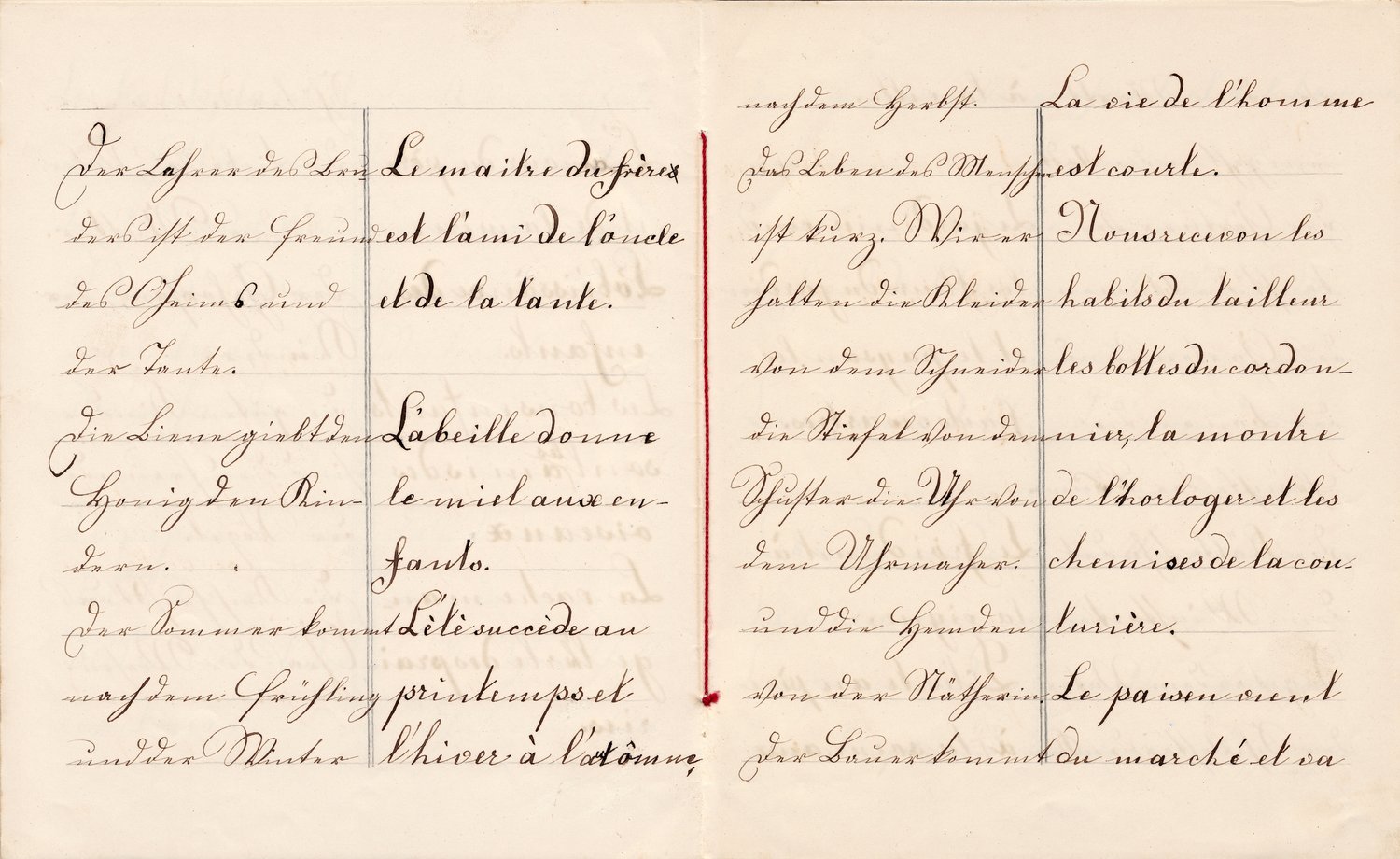

- Teach Word-Learning Strategies: Show students how to figure out unfamiliar words by teaching prefixes, suffixes, root words, and context clues.

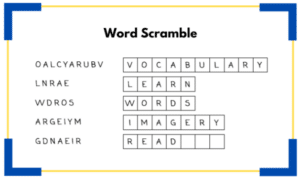

- Play Word Games: Games like Scrabble, Boggle, or vocabulary apps make learning fun and interactive.

- Talk About Words: Discuss interesting or unusual words during conversations at home or in the classroom. This builds curiosity about language.

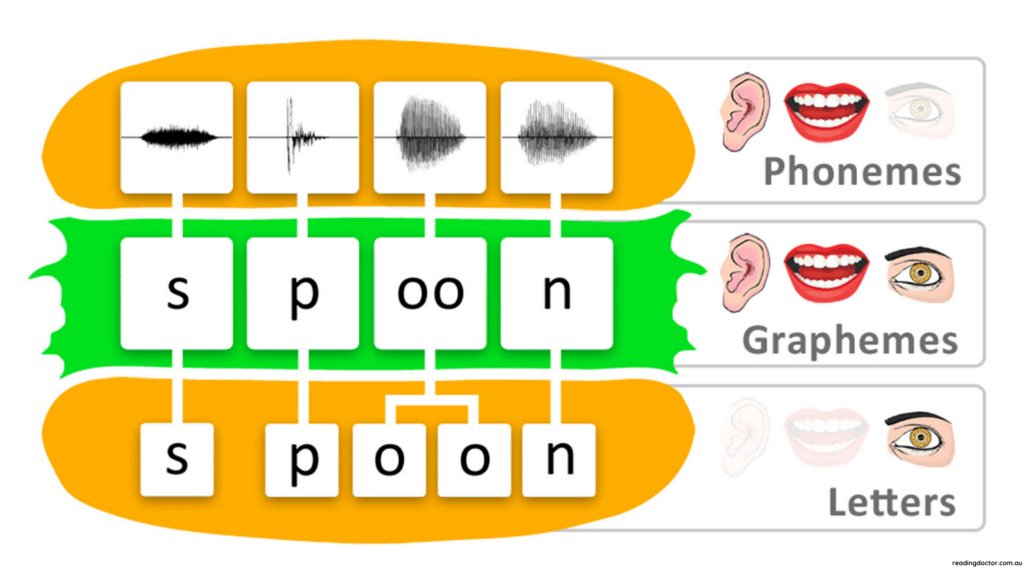

- Use Visual Imagery: Use visual imagery to create vivid mental images of vocabulary words. This taps into personal experience as well as visualization for better memory.

- Reinforce Through Writing: Encourage students to use new vocabulary in their writing. This strengthens understanding and helps solidify word meanings in memory.

Long-Term Benefits of a Strong Vocabulary

A strong vocabulary doesn’t just support reading comprehension—it’s a lifelong skill. From academic success to career readiness, vocabulary enables individuals to express themselves clearly, understand complex ideas, and engage with the world. It also enhances critical thinking and problem-solving abilities, which makes it a vital part of overall learning.

Final Thoughts

Building a strong vocabulary is an investment in a child’s success. By creating word-rich environments at home and in the classroom, parents and educators can empower young readers to thrive. Incorporating mental imagery techniques can make reading more vivid and memorable and turn every book into an adventure. The more words a child knows, the more opportunities they have—in books and in life.

If you or your child needs help with Reading Comprehension, we can help! Reach out to learn about our ReadingFish program for reading comprehension today!