The Schwa – or the lightly pronounced unaccented vowel sound

What is the Schwa?

Now that students have learned about multiple syllable words and syllable division with a variety of endings, they will be introduced to the ‘schwa’. The schwa is a lightly pronounced unaccented vowel sound that sounds like /u/ rather than the vowel saying its name or sound, and the ‘schwa’ is represented by an upside down ‘e’ (ə). The ‘schwa’ is a concept of our language that can be overlooked despite its prevalence in the English language.

Take for instance the word, ‘banana’; there are three of the same vowel in this word, but only one is actually pronounced with its sound – the other two are unaccented syllables, allowing the ‘schwa’ to occur (accented syllables will never be said with a schwa in English). Occasionally, the schwa can also be on a vowel digraph. An example of this would be in the word ‘captain’; if we said this word phonetically, the ‘ai’ in it would make a long /a/ sound, but we actually read it with an /ə/ sound.

History of the Schwa

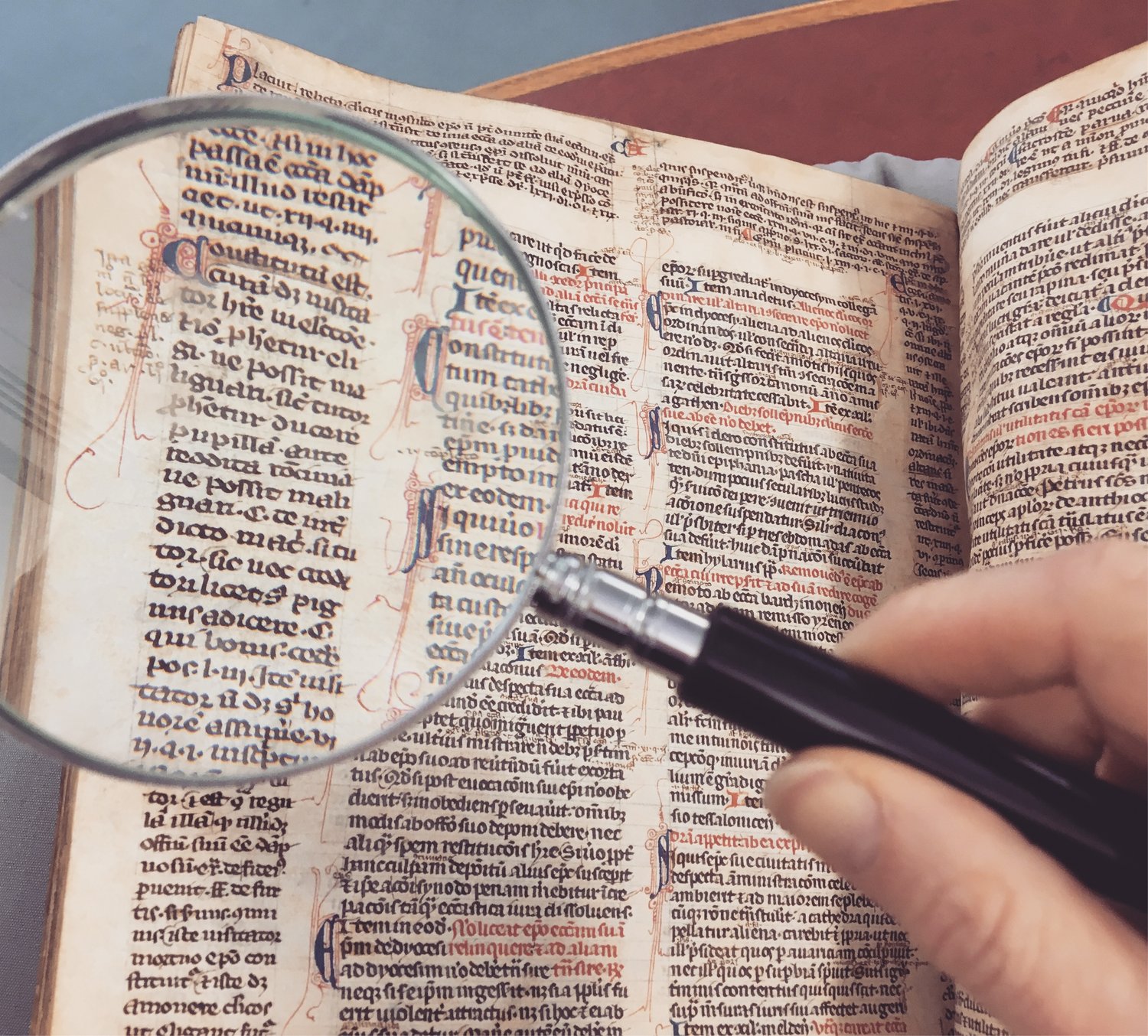

Where does the ‘schwa’ come from? The actual concept wasn’t coined as a ‘schwa’ until the late 1800’s by German phonologists and was borrowed from the Hebrew words “shva”, but the unstressed vowel sound goes back even further to Old English as well as languages of different families such as Albanian, Caucasian and Uralic languages, Hindi, Korean, Romance languages, Slavic languages, and many more all throughout the world!

There is always one stressed vowel within a multi-syllable word, so the unstressed vowel (or syllable) began to take on a consistent, unaccented sound /u/. English is a stress-timed language (opposite of a syllable-timed language, like Spanish), which means the rhythmic impression is based on the regular timing of stress peaks, not syllables. This style of English goes all the way back to the 9th century and is the same style that we use today.

The schwa is incredibly important for world languages in general by helping to emphasize the accented syllable. It might be hard to believe, but this sound is actually the most used sound in the entire English language.

How We Learn the Schwa

To help students understand the schwa and how to identify it within words, we draw the student’s attention to it with an example word, like ‘banana’ as it is easy to identify the schwa in this word. A clinician will write out the word and have the student divide it into syllables. Then, they ask them to identify the accent, which will play fair (in other words, it will say its expected sound).

Next, the clinician will draw the student’s attention to the unaccented syllables and identify the sound they are making as the schwa sound. It can be fun to have the student try the word without a schwa on the first and last syllable (e.g. bānanā). Next, the student will decode several words with the schwa sound repeating this process.

Step 1: Syllable Division

ba | na | na

Step 2: Identify Accent

ba | nà | na

Step 3: Draw Attention to Unaccented Syllables with Schwa Sound

bə | nà | nə

It may also be helpful to look up a few words in the dictionary to demonstrate how the schwa is represented so they can sound out unknown words. For example: captain (ˈkap tən), banana (bəˈna nə), abandon (əˈban dən). It will not be hard to find as it is in the majority of English words!