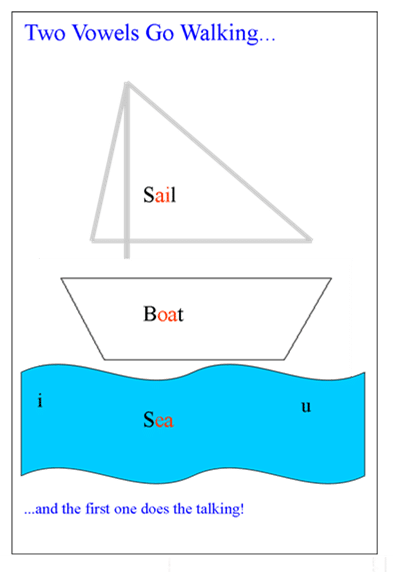

Two Vowels Go Walking

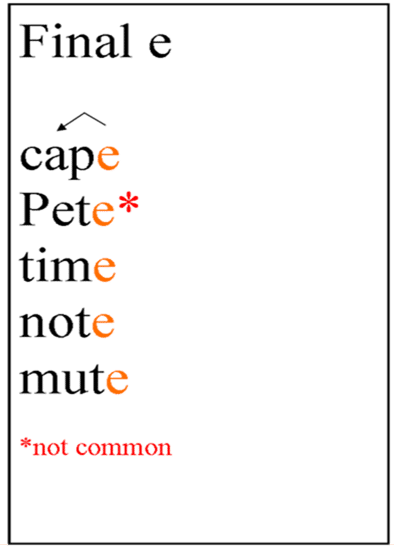

As we develop as readers, we begin to notice the various ways that vowels can combine to make new sounds. The next concept to introduce to students is the rule for “Two Vowels Go Walking” (TVGW). This rule allows us to introduce the vowel digraphs: ai, ea, oa. It always helps to begin with a review of the long vowel sound, and the rules we already know for making it (vowel+e, and final e). Next, we can establish that there are three additional ways to make long vowel sounds. The way we can remember these is with the saying: “When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking.” The talking in this instance is the first vowel making its long vowel sound. Be sure to touch on the fact that the ‘i’ and ‘u’ do not have a walking partner to help them say their name.

The following is an example dialogue for introducing the “Two Vowels Go Walking” rule:

When introducing Two Vowels Go Walking, it can be helpful to look at the limitations of the final e rule (that is, it can only jump over one sound). This primes the student for considering other ways that we can make a vowel say its name (without the use of the letter e).

Tutor: “Final E is a great way to make a vowel say its name, but it has a problem. The e can only jump over one consonant sound. So what do we do if we have two consonant sounds after the vowel?”

Student: “I’m not sure, but Final E won’t work.”

Tutor: “Today, we are going to learn about Two Vowels Go Walking. The great part about this rule is that it has a rhyme to help us remember the rule. It goes, “Two Vowels Go Walking and the first one does the talking.” To further help us remember the rule, we will draw a picture of a sailboat floating in the sea. Why do you think a picture would help us with this rule?

Student: “Because our brain thinks in images?”

Tutor: “You’re right! Anytime we can associate a picture with something, it makes it easier to remember. (The instructor draws TVGW card ) Let’s look at what we have here. I have three words in this picture: sail, boat, and sea. What vowel is saying its name in sail?

Student: “a”

Tutor: “Good. Now can you think of what vowel helps ‘a’ say its name in sail?”

Student: “i”

Tutor: “Fantastic! So now you can see how the rhyme works. Two Vowels Go Walking (A and I), and the first one does the talking. The ‘a’ gets to say its name.” Now, what vowel is saying its name in boat?

The tutor should repeat this process for the letters O and E (boat and sea.)

Tutor: “So now you can see that Two Vowels Go Walking helps us make vowels say their names when final e doesn’t work. But……Two Vowels Go Walking has a problem also.

Student: “Just what I need. MORE problems.”

Tutor: “The problem is that Two Vowels Go Walking doesn’t work for all of the vowels. ‘I’ and ‘U’ don’t get to say their names with TVGW. This is why the picture is so important. It helps us remember what vowels DO work with TVGW. So let’s show that by having the ‘i’ and ‘u’ floating in the sea.”