The Sound Symbol Association: what’s a sound, what’s a symbol, and how are they associated?

Of the multitudinous sounds human beings are capable of articulating, we have managed to set aside 44 of these to form the English language. 44 sounds may not seem like much, but the number of combinations possible with these sounds is potentially endless. So emerging readers need to be able to hear and make these individual sounds in words. They also need to blend these sounds together to form words. Humans are born with this ability, and spend their early childhood developing it.

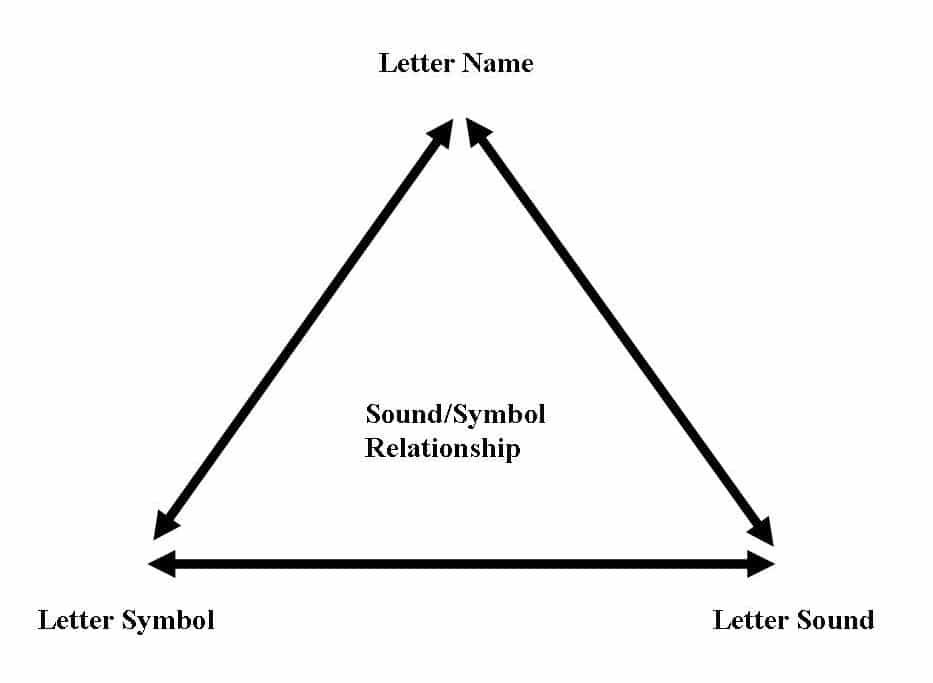

So emerging readers now have the ability to articulate and identify the 44 sounds (phonemes) of English. They are now prepared to further develop this ability (their phonemic awareness) by identifying these sounds with a letter name. Many readers begin to associate a name to a sound. For instance, they may say something like “the letter ‘a’ says /a/, like in apple.” What they are doing at this point is adding a new conceptual element to what was previously only a single sound. Sounds can now be identified with a name or label.

Next there comes the added difficulty of ascribing to these sounds a symbol. Emerging readers begin to see and distinguish a symbol (for example: a), recognize is as unique, and ascribe to it the correct label and sound. At this point, readers have connected to the three parts of the sound symbol association: the phoneme (sound), the grapheme (symbol), and the letter label or name. These three associations work in tandem for readers to absorb written language.

OK…here’s where things get a bit tricky. It would be nice if we lived in a world where each sound had a letter that matched up with it perfectly. Unfortunately, our world (and our languages) are a bit messier than that. English has an alphabet of 26 characters or symbols (a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z) This means we need to use these 26 symbols to show 44 sounds. Talk about making things difficult for the emerging readers out there.

We are going to eliminate 4 of these symbols right off the bat. C, Q, X, and Y are letter symbols with no sound identity (we’ll come back to these at a later point). This leaves us with 22 symbols to work with.

Now 5 of these symbols are going to represent vowels, so we can separate a, e, i, o, and u from the other symbols. Vowels are a special type of sound we make by opening our mouth and projecting a specific noise. Vowels use our voice to give body or force to words. The word vowel comes from the Latin word vocalis. This is where we get the English word vocal. A vowel gives voice to a words, and vocalizes it.

Once we take out the 5 vowel symbols, we’re left with 17 letters. (b d f g h j k l m n p r s t v w z) These letters are consonants. A consonant is made by articulating and stopping a sound. These sounds are made by specific mouth positions.

We take the 17 consonant sounds, and the 5 vowel sounds and we have 22 sounds. This means we’re halfway to 44. Now to get the remaining sounds in English we need to break the rules a bit and start combining letters together to make new sounds. When we do this we are making what is called a digraph. “Di” here means two, as in dihydrogen oxide (H2O), which is two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen. So digraph just means two letters acting as one unit.

There are 7 consonant digraphs. They are: th, sh, ch, wh, ng, th, zh. The last three can be a bit tricky. The sound for “ng” is similar to the end of the word “ring.” Also, “th” actually makes two sounds. It makes the soft /th/ sound as in the word “thin.” However, it will also make the hard sound /th/, as in the word “the” or “this.” We also have another problem. There is a sound that we make that is similar to the soft /sh/ sound. This is the hard /sh/ sound like in the word “Asia” or “casual.” There is no consistent letter combination for this sound, so we will represent it as “zh.” This is our first taste of multiple spellings of a sound. This can really trip up the emerging reader. We now we have the 7 consonant digraph sounds to add to our other 22 sounds, making a total of 29.

Whew, OK…

Up to this point we have only talked about the short vowel sounds (/a/, like in /a/pple, and so on). Next we need to talk about the long vowel sounds. The long vowel sound is when a vowel says its name. For example, the letter a can say /ae/ like in ate, aim, may, vein, weight, and so on. The letter e can say /ee/ like in eke, feet, sea, piece, and so on. The letter i can say /ie/ as in ides, light, pie, etc. The letter o can say /oe/ like in ode, oat, toe, and so on. The letter u can say /ue/ like in ute, glue, or Euro. As you can see, there are a lot of combinations of symbols to make the long vowel sound, but there are only five long vowel sounds. So we can add 5 long vowel sounds to go with the 5 short vowel sounds. With these 5 long vowel sounds, our total comes to 34.

We’re on the home stretch. Next we have the R controlled vowels. This includes 5 more sounds. There is /ar/, like car, /or/ like horn or door, /er/ like in hurt, bird, or term, /ār/ like in air or care, and /ēr/ like in ear or deer. Once again, like the long vowel sounds, there are multiple spellings for these sounds adding to the emerging reader’s trouble identifying these sounds. So with these 5 R controlled vowel sounds, our total is to 39.

Finally, we have 5 more sounds. We have /oo/, as in boot or moon. We have the “oo” sound /ʊʊ/, as in foot or book. These can be especially challenging as they are two separate sounds that are spelled the same exact way. There is /oi/ as in boil or toy, /ou/ as in pout or cow, and /au/ as in haul or paw. So adding in these 5 stragglers brings us to 44.

As you can see, sound symbol association is not a straightforward process. We have to allow for several sounds to be created, or associated with different combinations of letters. Also we occasionally have letter combinations stand for different sounds entirely. If the process itself wasn’t complex enough, you add into the mix the reality that every reader develops in their own way, and you can get a good deal of diversity in how people learn to read.

Many students we see struggle to some degree with sound symbol associations. This is the ability to identify a letter name and symbol(s) with a specific phoneme or sound. For some students, the struggle may be with auditory processing, where they are not able to correctly recognize and identify sounds they are receiving. Other students may have difficulty recalling specific information, such as a letter’s name, form, or sound. Regardless of the challenge, it is important that instructors are patient, playful, and are offering lots of positive praise.