Websites That Strengthen Reading Skills

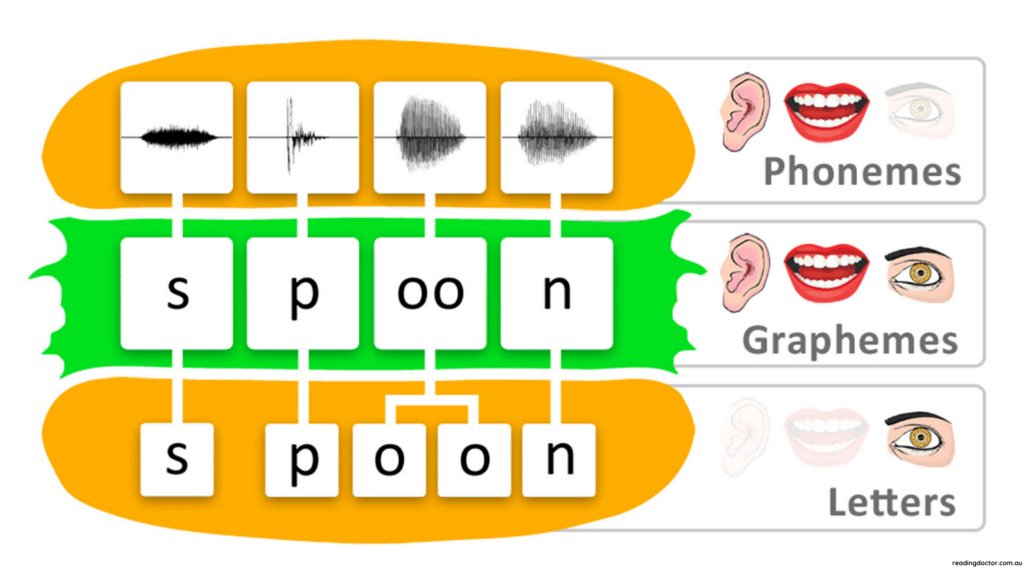

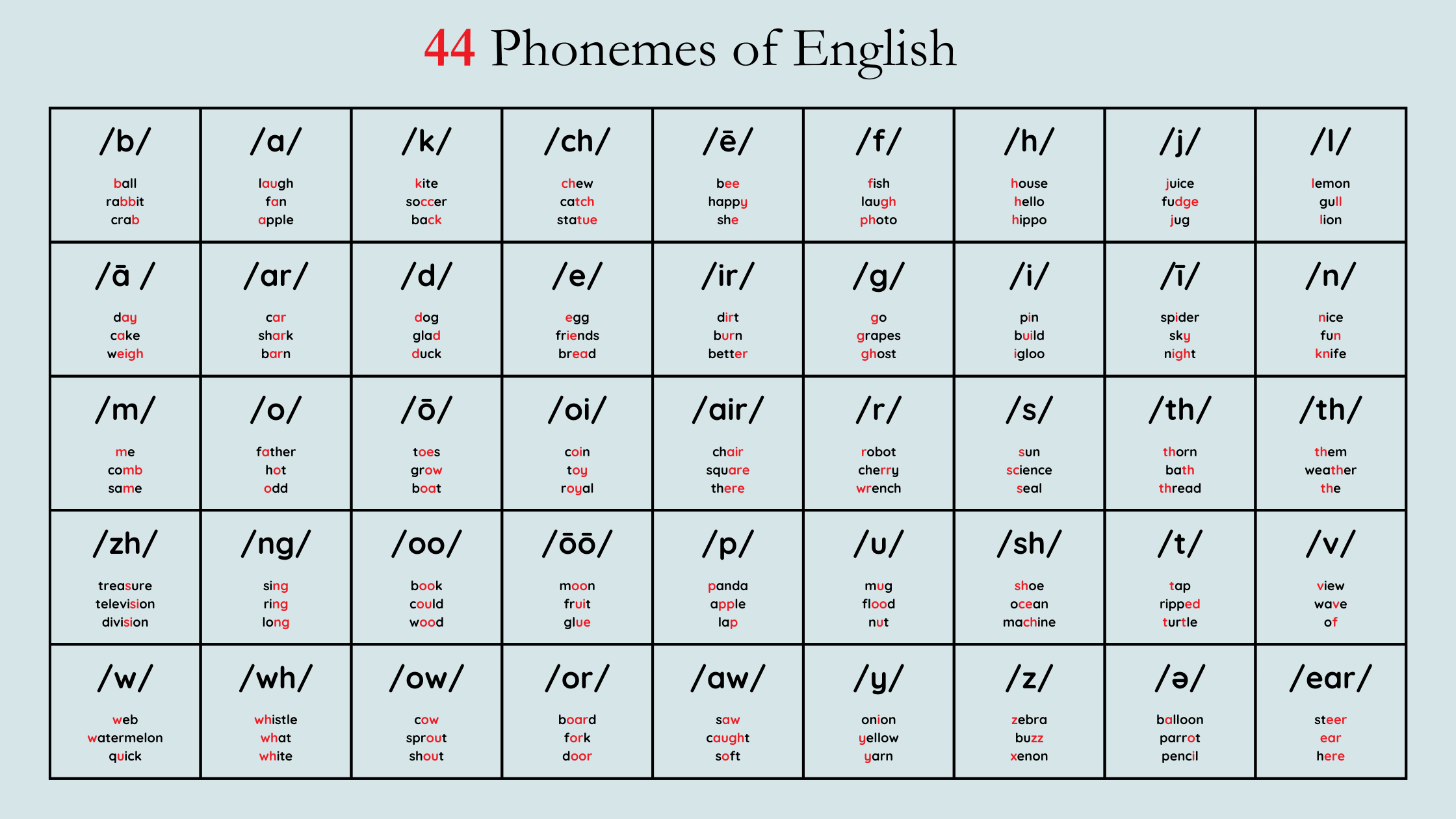

Building strong reading skills doesn’t have to feel like homework. With the right tools, students can practice phonics, decoding, spelling, and comprehension in playful, meaningful ways. Each resource below aligns with the Science of Reading and supports key literacy areas such as phonological awareness, orthographic mapping, vocabulary, and fluency

Starfall Education

Created by a doctor who overcame dyslexia, Starfall offers interactive games, songs, and books for grades K-5. Each activity is research-based and supports early literacy through systematic phonics practice and engaging repetition.

Education.com

After creating a free account, families can access an extensive library of reading games organized by grade level and skill area. It’s a great option for reinforcing comprehension and vocabulary between tutoring sessions.

IXL Language Arts

Covering pre-K through 12th grade, IXL combines quizzes, games, and progress tracking to help students master phonics, grammar, and comprehension at their own pace.

ABCya!

ABCya remains a classroom favorite for a reason — free, grade-based games that reinforce phonics, vocabulary, and fluency. Many games also integrate typing and grammar skills, making them a fun way to multitask learning.

Phonics and Stuff

Simple and teacher-friendly, this site includes printable phonics games, decodable books, and worksheets for emergent readers. It’s perfect for hands-on literacy centers or home practice.

Spelling City

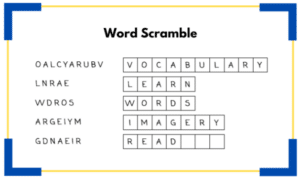

Also known as LearningWorks for Kids, this site builds spelling, phonics, and working memory skills through no-login games. Students can practice sound-symbol correspondence and word analysis while having fun.

Reading Eggs

With thousands of digital books and interactive lessons, Reading Eggs motivates young learners to read more often. Parents can track growth over time through a structured, phonics-based progression. Includes a free 30-day trial.

All of these programs support key Science of Reading principles:

-

Phonemic awareness: recognizing and manipulating sounds in words.

-

Phonics and decoding: connecting letters and sounds systematically.

-

Fluency and comprehension: practicing reading smoothly and with meaning.

-

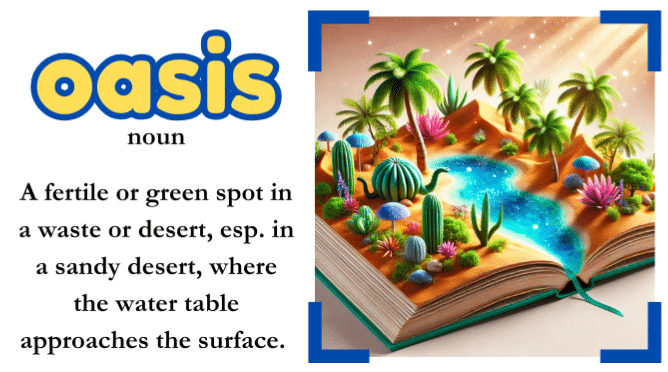

Vocabulary and spelling: reinforcing orthographic patterns through repetition and context.

Digital practice never replaces structured instruction — but it strengthens the foundation students build in one-on-one sessions. Used consistently, these tools can boost motivation, confidence, and reading independence.

Final Tip for Families

Pick two or three platforms to rotate each week. Pair 10–15 minutes of focused play with guided reading or structured literacy activities for the best results.

Happy Reading,

-CRC