The Building Blocks of Reading: Mastering the 44 English Phonemes

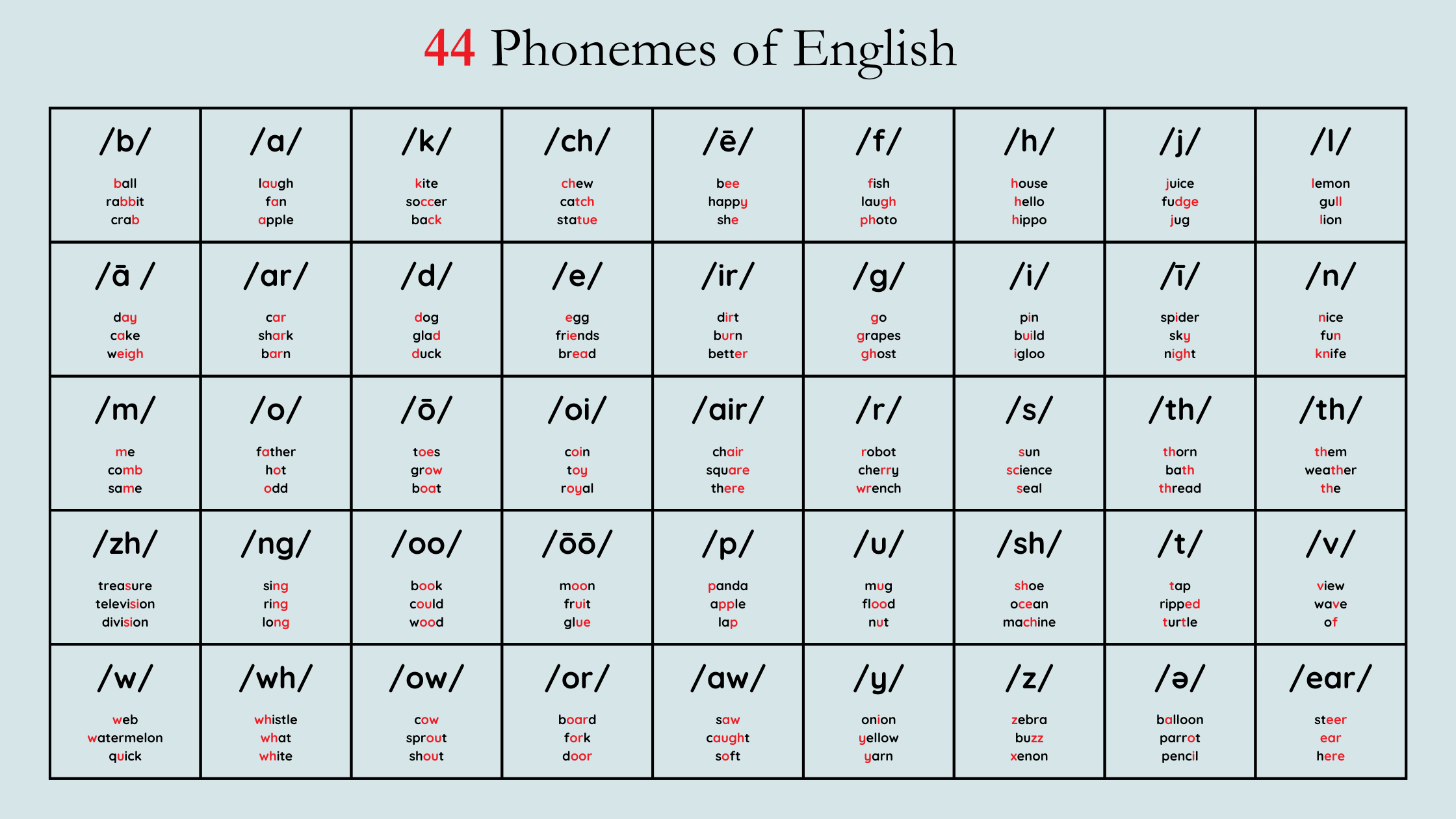

The English language is built on 44 distinct sounds, or phonemes, that form the foundation of how we read and speak. While this may seem like a manageable number, the combinations of these sounds create endless possibilities for words. For emerging readers, the journey begins with identifying, articulating, and blending these sounds to form words.

From Sounds to Symbols: The Basics of Reading

Step 1: Recognizing and Naming Sounds

From a young age, children naturally begin to recognize and produce the sounds that make up spoken language. They then connect these sounds to labels, such as recognizing that the letter ‘a’ says the sound /a/, like in “apple.” This process, known as phonemic awareness, sets the stage for reading.

Step 2: Linking Sounds to Symbols

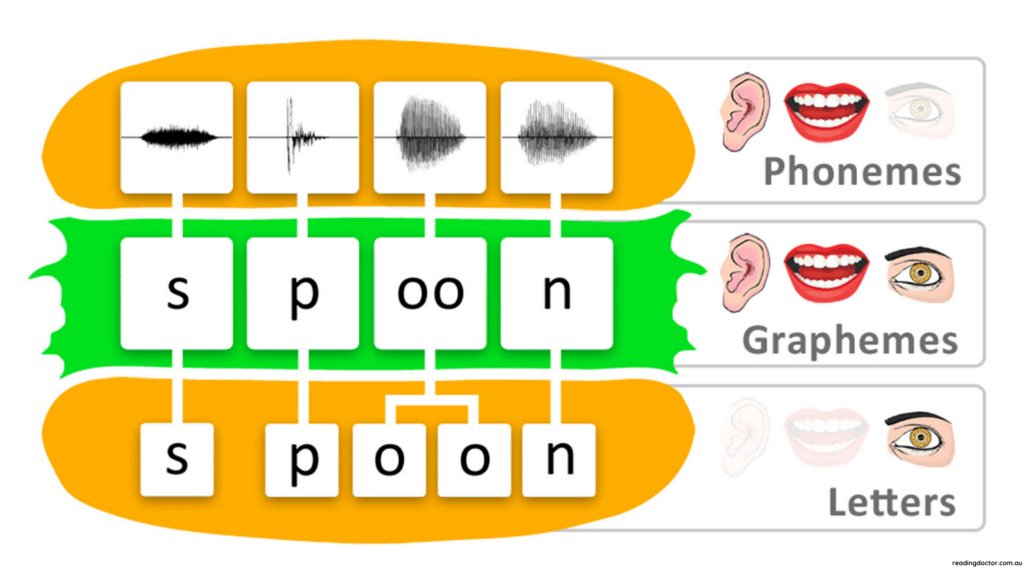

The next challenge is associating each sound with a visual representation—a letter or group of letters. This process involves three essential components:

- Phoneme: The distinct sound.

- Grapheme: The written symbol (e.g., the letter ‘a’).

- Letter Name: The spoken label for the grapheme.

This connection between sound, symbol, and label forms the foundation of reading and writing.

The Complexity of English Sounds

Vowels and Consonants

- Vowels: The five vowels (a, e, i, o, u) produce open, voiced sounds. For example, the sound /a/ in “cat” or /e/ in “meet.”

- Consonants: The remaining letters (e.g., b, d, f) produce sounds by shaping or stopping airflow.

Together, these letters create the basis for English sounds, but additional techniques are needed to cover all 44 phonemes.

Digraphs and Letter Combinations

To represent extra sounds, letters are combined into digraphs where two letters identify and represent a new, distinct sound. Examples include:

- Consonant Digraphs: th, sh, ch, wh, ng, th

- Vowel Digraphs: oo (boot), ee (meet)

Short and Long Vowels

Each vowel has a short and long sound. For instance:

- Short: /a/ as in “cat.”

- Long: /ae/ as in “cake.”

While the short sounds are represented by just the letter, the long sounds often involve multiple spellings. Weigh and way use different letters to spell the same sound /ae/, this adds complexity for learners.

R-Controlled Vowels

When vowels pair with the letter “r,” they take on unique sounds:

- /ar/ as in “car”

- /er/ as in “her” or “girl” or “turn”

- /or/ as in “porch”

Additional Sounds

English includes other sounds, such as:

- /oo/ as in “moon”

- /uu/ as in “foot”

- /oi/ as in “boil” or “boy”

- /au/ as in “haul” or “awe”

- /ou/ as in “out” or “wow”

These varied phonemes—and their often unpredictable spellings—require extra attention from both learners and instructors.

The Challenges of Sound-Symbol Association

For emerging readers, associating sounds with their corresponding symbols can be a hurdle. The same sound may have multiple spellings, and the same letter combination can produce different sounds. For example:

- /th/ sounds different in “thin” versus “that.”

Additionally, individual learners face unique challenges. Some may struggle with auditory processing, making it difficult to distinguish sounds. Others may have trouble recalling letter names, shapes, or corresponding phonemes. These challenges highlight the importance of patience, creativity, and positive reinforcement in teaching.

Tips for Supporting Emerging Readers

- Be patient: Every learner progresses at their own pace.

- Use multi-sensory activities: Engage sight, sound, and touch to reinforce letter-sound connections.

- Celebrate progress: Positive feedback builds confidence and motivation.

- Practice consistently: Regular practice with fun and engaging activities solidifies learning.